Under California law, most licensed contractors or suppliers that provide labor, services, equipment, or materials on projects involving the common area of a community association are entitled to record a mechanic’s lien or issue a stop payment notice if they are not paid for their work or materials. Associations involved in such projects often receive 20-day “preliminary notices” from vendors and wonder what they are and what, if anything, they are supposed to do with them. Contractors are required to send these preliminary notices to associations to preserve their rights to record mechanic’s liens or issue stop payment notices. The preliminary notice must contain certain information, including a description of the nature and estimated cost of the work, the identities of the parties, and the location of the property in question, as well as a boldfaced “Notice to Property Owner” statement. Contractors that are under direct contract with an association (such as a “general” contractor that hires subcontractors aka “subs” for a project) are not required to serve a preliminary notice on the association, because the association is presumably already aware of all of the information that a preliminary notice would otherwise contain. Direct contractors are instead required to serve preliminary notices on the actual or reputed construction lender for the project.

Under California law, most licensed contractors or suppliers that provide labor, services, equipment, or materials on projects involving the common area of a community association are entitled to record a mechanic’s lien or issue a stop payment notice if they are not paid for their work or materials. Associations involved in such projects often receive 20-day “preliminary notices” from vendors and wonder what they are and what, if anything, they are supposed to do with them. Contractors are required to send these preliminary notices to associations to preserve their rights to record mechanic’s liens or issue stop payment notices. The preliminary notice must contain certain information, including a description of the nature and estimated cost of the work, the identities of the parties, and the location of the property in question, as well as a boldfaced “Notice to Property Owner” statement. Contractors that are under direct contract with an association (such as a “general” contractor that hires subcontractors aka “subs” for a project) are not required to serve a preliminary notice on the association, because the association is presumably already aware of all of the information that a preliminary notice would otherwise contain. Direct contractors are instead required to serve preliminary notices on the actual or reputed construction lender for the project.

On the other hand, contractors that are not under direct contract with an association, such as subcontractors, must serve a preliminary notice on the association, the actual or reputed direct contractor for the project, and any actual or reputed construction lender. Therefore, most preliminary notices that associations receive will be from subcontractors. Generally, preliminary notices are sent via first-class registered or certified mail, express mail, or overnight delivery. As long as an association recognizes the information in the preliminary notice, generally speaking there is nothing special that it needs to do, as serving a preliminary notice on an association does not change a contractor’s rights, it merely preserves them. Sometimes, contractors request that an association acknowledge in writing that they received a preliminary notice. While signing such a preliminary notice is generally unnecessary, an association may choose to do so anyway, as a courtesy and to keep the project moving.

HOA Law Blog

HOA Law Blog

The spread of the coronavirus/COVID-19 has caused and will likely continue to cause unexpected interruption in the business of many California community associations. Many of our association clients are in the middle of large common area refurbishment and restoration projects. With increasing restrictions and/or recommendations by public officials and others intended to control the spread of the coronavirus, contractors/vendors may suspend or cease services/work and advance “force majeure” as a defense to the association’s breach of contract claim. It is important that board members and managers understand what force majeure means and how to respond when a contractor/vendor suspends or seeks to suspend their performance due to the coronavirus citing a force majeure clause contained in the contract between the association and the contractor or vendor.

The spread of the coronavirus/COVID-19 has caused and will likely continue to cause unexpected interruption in the business of many California community associations. Many of our association clients are in the middle of large common area refurbishment and restoration projects. With increasing restrictions and/or recommendations by public officials and others intended to control the spread of the coronavirus, contractors/vendors may suspend or cease services/work and advance “force majeure” as a defense to the association’s breach of contract claim. It is important that board members and managers understand what force majeure means and how to respond when a contractor/vendor suspends or seeks to suspend their performance due to the coronavirus citing a force majeure clause contained in the contract between the association and the contractor or vendor.

You may have heard an attorney refer to the “SB800 process” and not really understood what it was all about. SB800 refers to a California Senate Bill that became law about ten years ago, requiring and setting out a new procedure that had to be followed for construction defect claims and lawsuits against the builders and developers of condominium and homeowner associations. SB800, which was codified in Civil Code § 875 et seq., applies to homes and condominiums and provides the procedure for instituting construction defect claims for new residential property “sold” on or after January 1, 2003. Although the express legislative intent of SB800 was to improve standards and procedures for the administration of civil justice and early resolution of construction defects, according to the California Building Industry Association, SB800 would lead to increased production of affordable condominiums and townhouses. Not sure if that actually happened. But it is clear that a lot of condos have been built in the last ten years. This bill significantly changed the way defect cases were being handled.

You may have heard an attorney refer to the “SB800 process” and not really understood what it was all about. SB800 refers to a California Senate Bill that became law about ten years ago, requiring and setting out a new procedure that had to be followed for construction defect claims and lawsuits against the builders and developers of condominium and homeowner associations. SB800, which was codified in Civil Code § 875 et seq., applies to homes and condominiums and provides the procedure for instituting construction defect claims for new residential property “sold” on or after January 1, 2003. Although the express legislative intent of SB800 was to improve standards and procedures for the administration of civil justice and early resolution of construction defects, according to the California Building Industry Association, SB800 would lead to increased production of affordable condominiums and townhouses. Not sure if that actually happened. But it is clear that a lot of condos have been built in the last ten years. This bill significantly changed the way defect cases were being handled.  I recently read with interest an article prepared by an attorney that represents developers with the title “Residential Real Estate: Lessons From The Recession” written by attorney Nancy Scull, who represents developers. Her article commented on the fact that it was not that long ago that we were hearing new stories about “broken projects” and “fractured condominiums” which she described as the “remnants of the residential communities that fell victim to our most recent real estate recession.” It has been awhile since we heard about condominium or other homeowner association developments that were not completed and were abandoned by developers in the wake of the Great Recession. But as our economy and the real estate market continues to recover, the projects are being reevaluated, and new real estate development projects are being started. As Ms. Scull suggests, “with such positive news, it is easy to forget the problems and challenges that confronted residential developers only a few years ago. Real estate is cyclical, and the failure to learn from the residential housing economic downturn may only result in history repeating itself when the inevitable real estate ‘bubble’ bursts.”

I recently read with interest an article prepared by an attorney that represents developers with the title “Residential Real Estate: Lessons From The Recession” written by attorney Nancy Scull, who represents developers. Her article commented on the fact that it was not that long ago that we were hearing new stories about “broken projects” and “fractured condominiums” which she described as the “remnants of the residential communities that fell victim to our most recent real estate recession.” It has been awhile since we heard about condominium or other homeowner association developments that were not completed and were abandoned by developers in the wake of the Great Recession. But as our economy and the real estate market continues to recover, the projects are being reevaluated, and new real estate development projects are being started. As Ms. Scull suggests, “with such positive news, it is easy to forget the problems and challenges that confronted residential developers only a few years ago. Real estate is cyclical, and the failure to learn from the residential housing economic downturn may only result in history repeating itself when the inevitable real estate ‘bubble’ bursts.” Many owners buy units, lots or homes at community associations that have views and are later shocked to learn that the view they cherish, the view that caused them to buy that home, is not guaranteed. The question that has been posed is whether or not property owners are entitled to an unobstructed view. With some exceptions, the answer in California is “no.” The California Supreme Court spoke on this subject in the late 19th century case of Kennedy v. Burnap and established the doctrine in California that one’s ownership of land does not imply a right to force owners of neighboring land to refrain from obstructing the view from the land or the light and air reaching the land. This law has not changed all that much since that case was decided in 1898.

Many owners buy units, lots or homes at community associations that have views and are later shocked to learn that the view they cherish, the view that caused them to buy that home, is not guaranteed. The question that has been posed is whether or not property owners are entitled to an unobstructed view. With some exceptions, the answer in California is “no.” The California Supreme Court spoke on this subject in the late 19th century case of Kennedy v. Burnap and established the doctrine in California that one’s ownership of land does not imply a right to force owners of neighboring land to refrain from obstructing the view from the land or the light and air reaching the land. This law has not changed all that much since that case was decided in 1898.

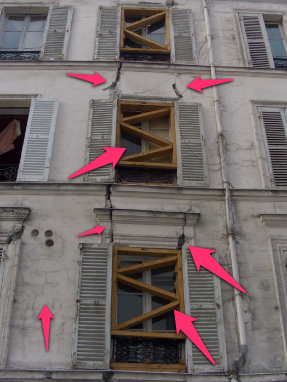

I recently read an interesting article in the newspaper regarding structural defects. The article entitled “Home Structural Defects Are Rare But Can Be Costly” provides good advice for both homeowners and condo owners and associations.

I recently read an interesting article in the newspaper regarding structural defects. The article entitled “Home Structural Defects Are Rare But Can Be Costly” provides good advice for both homeowners and condo owners and associations.  On occasion, we deal with slope and water runoff issues, as a result of poorly installed drainage or otherwise, between neighboring associations, a sub and a master association, or with owners. We have found that it is a common misconception that the law provides that where neither party has done anything to specifically cause or exacerbate the water runoff, the upstream property owner has a responsibility to take care of any damage suffered by the downstream property owner as a result of the runoff. The concept that the upstream property owner is strictly liable for the runoff of water emanating through or by its property is not correct. This misconception appears to be the result of confusion between the traditional rule of liability with the current law on liability as it relates to real property matters.

On occasion, we deal with slope and water runoff issues, as a result of poorly installed drainage or otherwise, between neighboring associations, a sub and a master association, or with owners. We have found that it is a common misconception that the law provides that where neither party has done anything to specifically cause or exacerbate the water runoff, the upstream property owner has a responsibility to take care of any damage suffered by the downstream property owner as a result of the runoff. The concept that the upstream property owner is strictly liable for the runoff of water emanating through or by its property is not correct. This misconception appears to be the result of confusion between the traditional rule of liability with the current law on liability as it relates to real property matters.